Better Calendars

Better Calendars

Adam Kall, Co-Founder & Director of Science

9 minute read

Telling time is simultaneously an incredibly important part of human civilization, and one that we historically have often gotten wrong. For much of human civilization, concepts like seconds and minutes were only used in very specific applications and with wildly different degrees of accuracy. For the average ancient farmer, telling time was as simple as checking if the sun had risen, if it had reached the highest point in the sky, or if it had set. This was good enough for the more equatorial regions, which had only mild swings between the seasons, but when humans started moving to river valleys and farther north, they had to contend with the new concept of seasons. Even as fewer people work as farmers in the modern day, telling time remains an important system for civilizations, with many improvements and changes being made over the years, ending in the modern Gregorian calendar. The first improvement to get to the present calendar was attempting to predict when the weather would change, that is, what we have termed seasons.

Seasons provide an introduction to one of the most annoying aspects of keeping time over long periods; the rotation of the Earth to create a day and the orbit of the Earth to create a year have no influence on each other. This means that when humans tried the very reasonable idea of counting the days, their calendars would end up getting out of sync with the season after a generation or two. Thankfully there are checkpoints during every year known as the solstice, which is either the longest or shortest day of the year. In case it isn’t evident, the Sun’s apparent pace across the sky does not change throughout the year, so what actually causes the lengthening or shortening of the days is just how high the Sun gets in the sky as it arcs over. A very low Sun will only appear for a few hours, indicating a short day, while an extremely long day will have the sun travel far overhead and only dip below the horizon for a bit. So for ancient people, they could put a stick in an open field and keep track of how the shadow grew and shrank, measuring the shortest shadow of each day. When you had a day with the shortest short shadow, or longest short shadow, you had a solstice.

So the problem is solved! We can just have the one villager who is not talented at anything else sit and watch a stick every day of every year, counting the days since the last solstice, and then ring a bell or start a big bonfire whenever a solstice is reached. And believe it or not, this was actually not far off from the strategy employed for thousands of years and is part of the root around many winter and summer celebrations. However, as civilizations grew larger and more complex, precise date-keeping became necessary, and many calendars were created to count the days and years. Since trying to count to 365 was somewhat difficult and prone to miscounting, the first step for calendars was to break them down into smaller portions, known as months. If you haven’t already spotted it, “month” comes from the same root as “moon,” because that was originally how calendars kept track of months. These calendars tracking lunations did an alright job, but the moon orbits in 29.5 days, so some months would have 29 days and others have 30 days, alternating to keep aligned with the moon. Unfortunately, neither 29 or 30 divide 365 evenly, so the lunar calendars would quickly fail in their most important task of tracking the seasons.

It was with the Roman Empire that the first widely used solar calendar was introduced. There had been other solar calendars prior to this, but the Roman calendar was the most popular and several aspects still influence the calendar of today. First was the introduction of a leap year every 4 years, since there are actually 365.24 days in a year that keeps the calendar aligned for a very long time. Second was that a lot of Roman Emperors decided they were so important that a whole month should be named after them (say hello to July for Julius Caesar and August for Augustus). It actually wasn’t the fault of these two for extending the calendar by two months, but the second king of Rome who added January and February into the mix, shifting from a nice 10-month grouping with months alternating between 36 and 37 days, into a 12-month calendar of 30 and 31 days with a random February thrown in for 28 days. Just to add to my calendar-loving pain, we now have September, with the root Sept- meaning 7, as the 9th month, Octo- meaning 8 as the 10th month, Novem- meaning 9 as the 11th month, and Decem- meaning 10 as the 12th month. Thankfully this cycle of wrongly rooted months was shortened slightly by July and August replacing Quintilis and Sixtilis, names implying 5th and 6th for the 7th and 8th months respectively. For completeness, January through June are all named after Roman gods, so that’s fun in a world with few remaining Hellenic worshipers.

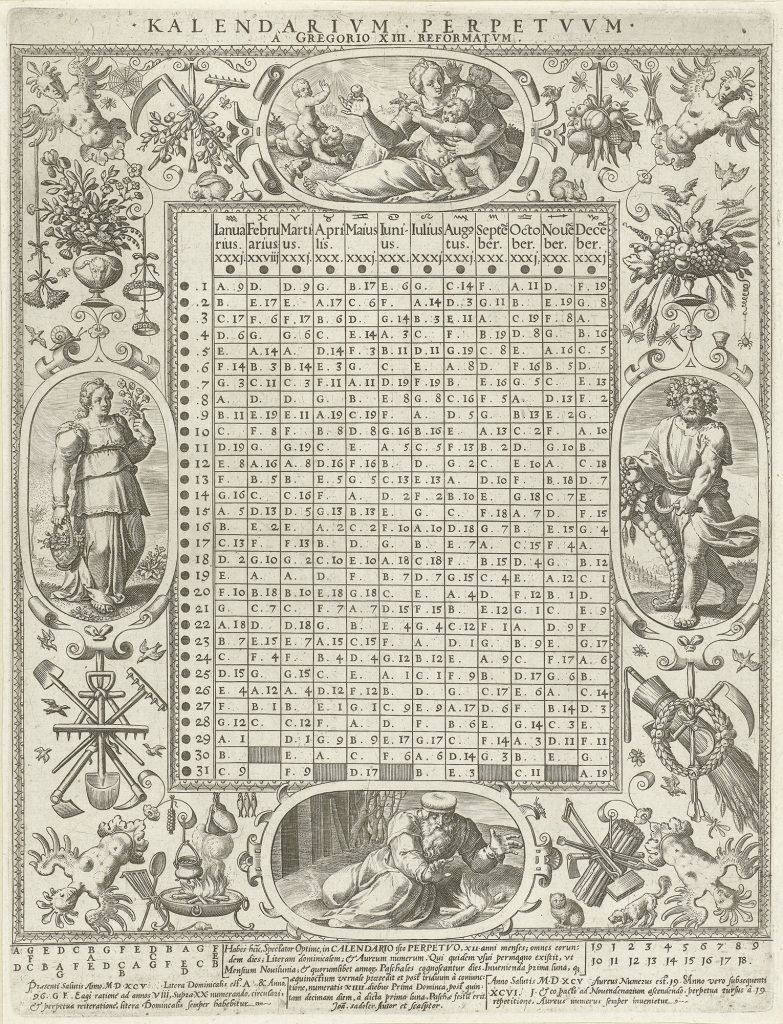

Alright, I’ve ranted long enough about the messy beginnings of our calendar, time to get to the core issue: who is Gregory and why did everyone love his calendar? Well specifically he is Pope Gregory XIII who made the Gregorian calendar in 1582 and it added one very important rule to the solar calendar. Now the leap years would be skipped on years divisible by 100, but we skip the skip, or still have the leap year, if it is divisible by 400. So 1900 was not a leap year, but 2000 was, and 2100 won’t be again. A helpful act achieving even greater accuracy in timekeeping, this was all so the Spring equinox would stop drifting away from March 21st and the Catholic church could calculate Easter correctly. What followed next was a lot of imperialism and the sharing of the calendar with the whole world, most of which accepted it and some of which held strong to their own specific calendar versions for keeping time for civil obligations (looking at you Ethiopia, Nepal, Iran, and Afghanistan).

So now we’re in the 21st century and nearly the whole world is on the same calendar. This should be cause for celebration at the ability of the human race to come together, except I’m not celebrating too much. The calendar is a mess, with inconsistencies and leftovers from long ago that make a question like “what day of the week is February 14th?” a very difficult question to answer without referencing a calendar. Also, even the year in the Gregorian calendar is confusing with the distinction of BC and AD (or BCE and CE) because the line they draw is a very vibrant time in human history and it becomes unnecessarily complicated to see that Rome was pillaged in 390 BC and 410 AD and know that is 800 years of difference and not 20. So let's fix both of these issues, starting with the years as it is the easiest.

To preface, I have nothing against the fact that the creators of the Gregorian calendar were Christian and wanted to denote the birth of Jesus as a special turning point in time. However, they got it wrong. Most modern Biblical scholars agree Jesus was born between 6 BC and 4 BC (timing the birth with being before or around the death of King Herod). Due to that original error, in my mind, there should be room to provide a small change. The proposal, of which I am not the originator, is to add 10,000 years to the calendar to align our “zero” year with another significant event in civilization’s history. That would mean next year isn’t 2024, but 12024. The 10,000 is nice because the change requires only the addition of a “1” to the front of our modern years, and if we go back 12,000 years that is the very beginnings of humans coming together in long-lasting communities and beginning to record things. So now the calendar can be used to date all known significant individual events, and for the rest, we can just say 3.4 million years ago like we currently do. As an added bonus, we can keep the Gregorian rules about leap years because they still work just as well.

Now for the months, which is going to be a bit tricky. The main aspect we can’t adjust is that there are 365.2425 days per year, which after keeping the Gregorian strategy for leap years means we need to fit 365 days +1 sometimes into a calendar. The months are a good idea, because again counting to 365 is hard, as well as keeping the concept of weeks so we can maintain the idea behind work days and weekends. What can change is the number of days in these units, so let's look at ways to break down 365. In a trick from number theory, every number can be broken down into its prime decomposition, or the prime numbers that multiply to create the bigger number. These primes and all their combinations will then give us all the divisors for the bigger number. With 365, the prime decomposition is 5 and 73, so we can have 5 months with 73 days in each, and 73 weeks with 5 days in each. Gross.

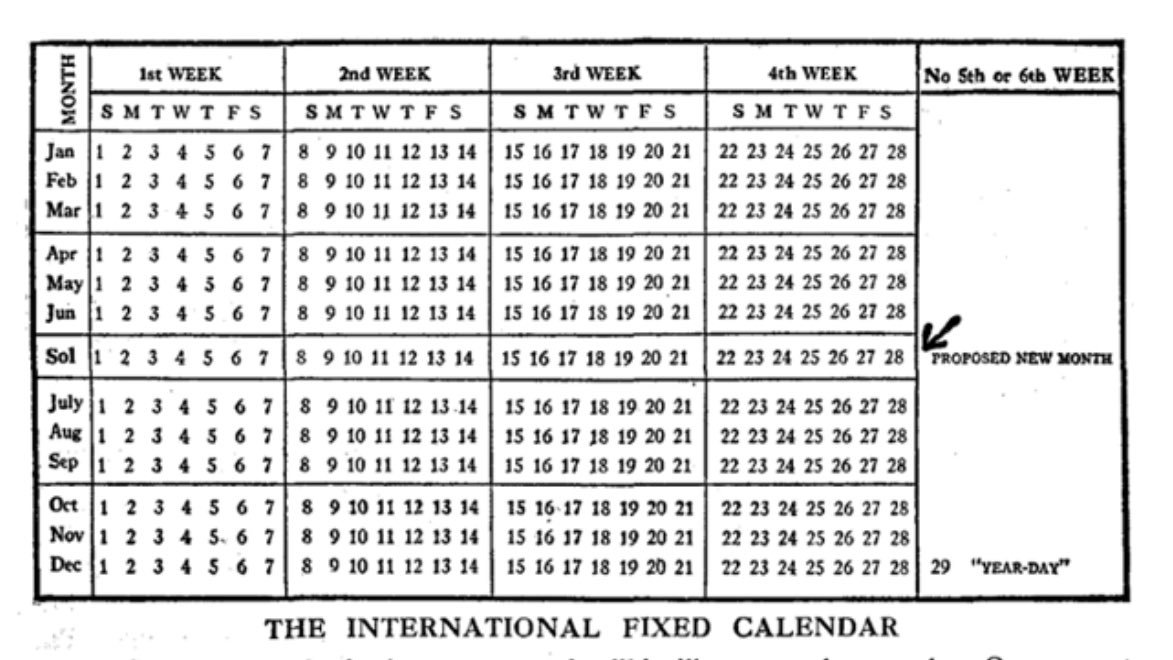

Let’s try something clever. Since 365 is not a great number of days, what about trying 364 days and we just have to figure out what to do with the remaining day later. With 364 the prime decomposition is 2, 2, 7, and 13, which means we can divide 364 by 2, 4, 7, 13, 14, 26, 28, 52, 91, and 182. Already this is looking a lot better since 7 and 52 are in the list so we can keep the length of the week and the number of weeks exactly the same. For months we don’t see 12, 30, or 31, but we do have 13 which is close. If 364 is divided by 13 we get 28, which just so happens to be divisible by 7. So we could divide 364 into 13 months and each month would have exactly four weeks in it, with each date occurring on the same day of the week. Ponder this for a moment. That means that whenever someone says the 8th you immediately know it will be the second Sunday of the month. If you get paid bi-weekly then every month has exactly 2 paychecks rather than random months having 3. This would mean one more monthly rent payment per year, so society would have to negotiate that with the landlords, but it would at least mean if your rent is due on the 16th of every month you always know that will be the Monday following the first two weeks and your first paycheck of the month. It would be a fixed calendar. Your birthday and anniversary would also occur on the same day, for better or worse, and holiday breaks would occur like clockwork. Pretty solid and consistent if you ask me.

But what to do about that final day? A year is still 365 days long and we don’t want the calendar speeding up relative to the seasons by one day a year, plus the leap years can’t fit anywhere without screwing up the beautiful order. The final piece to this brilliant puzzle is to just put the extra day (or days on a leap year) at the end of the calendar in a special New Year zone. This zone has no day of the week, or number of the month, or time associated with it, it is just null. So almost a guarantee it would be a holiday for almost everyone since if you work the weekends or weekdays, this would be neither of them. We’d probably all get together and just throw a party, which we don’t even need to have at the end of the year when, at least here in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, it gets really cold. The beauty of having a New Year Zone is that it can go anywhere, as long as everyone agrees. So it could go with the summer equinox, or after a particularly hard Wednesday, or on Taylor Swift’s birthday (suggestion from my wife). My personal suggestion is to place it on the fall equinox, which would be close enough to put the New Year Zone after the second week of November, now the 9th month in the calendar.

Writing this column was, ironically, a battle against time. We knew we wanted to post it around New Year's given the relevance, but as I started writing and researching I continued to find ever more tangents to dive down. I didn’t even get to delve into telling time on other planets or how to know your own age when the time dilation of interstellar travel is involved, but that’s also fine because we haven’t really solved those problems yet either. Instead, I hope you’ve enjoyed reading about the fascinating origins of our modern, widely accepted calendar and weren’t too offended by my suggestion of a more mathematically optimal distribution of months. Keeping track of time will go on forever, in some form, as long as humans are around to measure it, but to ensure this column doesn’t also continue forever, I want to wish you a happy 12,024 from all of us here at KMI.

Recommended column to read next: Spooky Space: Halloween on the ISS